I went for the birds and the blossoms, but forgot about the bugs. They didn’t deter me, however.

My neighbor had told me that the Mountain Laurel bushes were blooming at various locations in Shenandoah National Park, just a short drive from my home. The laurel blooms from late May into mid-June, depending on elevation.

Of course, I had to see for myself. I fixed a hiker’s lunch, packed my binoculars, camera, and a couple of jackets, and headed out. It’s often 10 degrees or more cooler in the mountains than in the Shenandoah Valley, where I live.

I didn’t need to bother with the jackets. The temperature was 70 degrees when I arrived, and it was humid, with little to no breeze. It was 79 when I left.

A small black bear cub greeted me not long after I entered the park. Fortunately, it scampered back off the old stone wall away from the road and into the forest.

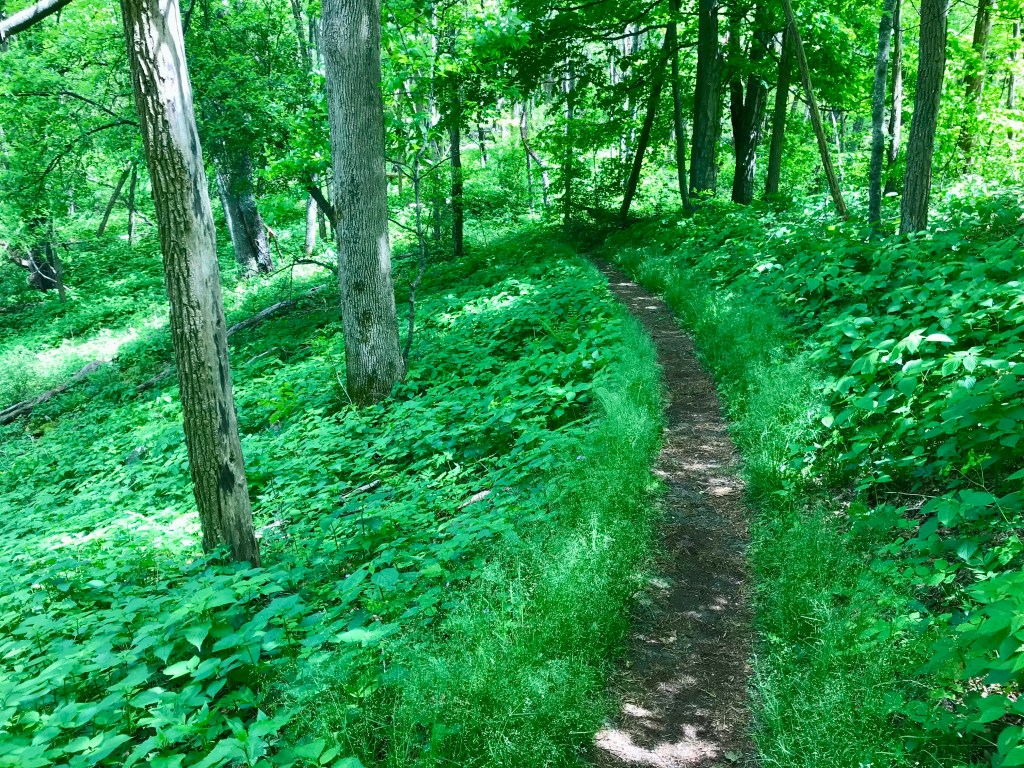

I soon reached my first destination. Just a short distance off Skyline Drive, I reached the Appalachian Trail, which crossed a fire road. I didn’t see any Mountain Laurel, but songbirds were plentiful. So were the knats and mosquitoes.

I strolled along the AT, swatting at the pesky bugs and trying to locate the many warblers I was hearing and recording on my smartphone’s birding app. Singing its unmistakable “drink your tea” melody, a male Eastern Towhee posed for a photo on a limb hanging right over the trail.

I met a lone through-hiker from South Carolina. She hoped to reach Mt. Kadadhin in Maine by mid-September. She told me she had passed many stands of Mountain Laurel on her hike so far, which began at the Appalachian Trail’s traditional starting point, Springer Mountain, in Georgia.

She headed north while I retraced my steps to my vehicle. The birdsong was terrific, but the forest’s full foliage made it challenging for this old guy to spot the warblers as they flitted from one branch to another, munching on their insect smorgasbord.

Besides, my main goal was to photograph the blooming Mountain Laurel. I followed my neighbor’s directions to another section of the AT, where the Mountain Laurel was so prolific that it formed a floral tunnel.

The laurels were in all stages of blooming, from tight pink buds to hexagonal flowers in full bloom. In places, the sun filtered through the forest canopy, highlighting the beauty before me.

The laurel blooms offered no fragrance, and I never saw an insect of any kind on any of the hundreds of blossoms. There was a good reason for that. As pretty as the prized flowers are, they are poisonous to any living creature. Every part of the plant is toxic.

So, if someone offers you Mountain Laurel honey, politely decline. Merely enjoy the flowers with their evergreen leaves. If you go, make sure you take your favorite bug spray.

© Bruce Stambaugh 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment.